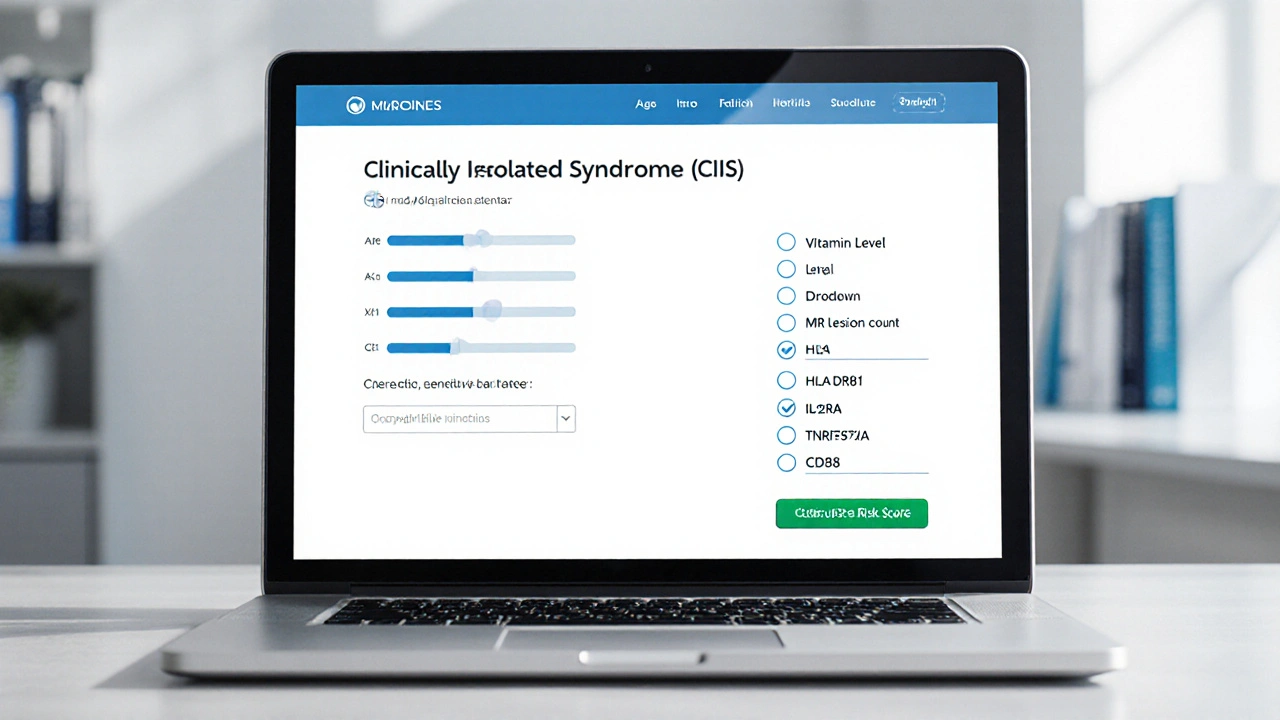

Clinically Isolated Syndrome (CIS) Risk Calculator

This tool estimates your risk of developing Multiple Sclerosis (MS) following a Clinically Isolated Syndrome (CIS) episode. Your risk depends on genetic factors, MRI findings, and lifestyle variables.

Enter your information and click "Calculate Risk Score" to see your estimated risk of converting from CIS to MS.

Quick Takeaways

- Clinically Isolated Syndrome (CIS) is often the first clinical hint of multiple sclerosis (MS).

- Genetic factors account for roughly 20‑30% of the risk of converting from CIS to MS.

- Key genes such as HLA-DRB1 (especially the *DRB1*·15 allele) heavily influence immune response in demyelinating disease.

- Environmental triggers-low vitamin D, EBV infection, smoking-interact with genetics to shape outcomes.

- Genetic testing is optional; a family history plus a personalized genetic risk score can guide monitoring decisions.

What Is Clinically Isolated Syndrome?

When a patient experiences a single episode of neurological symptoms that point to inflammation or demyelination in the central nervous system, doctors label it Clinically Isolated Syndrome (CIS) - a one‑off event that meets the diagnostic criteria for a possible future multiple sclerosis attack. The episode could be optic neuritis (vision loss), a sensory tingling, or a brief motor weakness. MRI often shows one or more lesions, but not enough to meet full MS criteria.

Why does CIS matter? About 30‑50% of people with CIS will develop MS within five years, but the exact odds depend on age, lesion load, and - crucially - genetics. Understanding the genetic backdrop helps clinicians and patients anticipate that conversion risk and tailor follow‑up MRI schedules.

Genetics 101: How Heredity Shapes CIS

Genetics isn’t destiny, but it does set the stage. Twin studies from the 1990s showed that identical twins share a 25‑30% concordance rate for MS, while fraternal twins only share about 3‑5%. Those numbers hint at a modest yet measurable hereditary component. Modern genome‑wide association studies (GWAS) have identified more than 200 loci linked to MS risk, many of which also influence CIS outcomes.

Think of genetics like a set of dice. Each risk allele rolls a small number; together they add up. A single allele rarely decides anything, but a cluster of them can tip the balance toward a higher likelihood of converting from CIS to MS.

Key Genetic Players Linked to CIS

Below is a snapshot of the most consistently replicated genes that impact CIS risk and conversion rates.

| Gene / Locus | Risk Allele | Effect on CIS → MS Conversion |

|---|---|---|

| HLA-DRB1 (major histocompatibility complex class II) | DRB1*15:01 | ~2‑3× higher odds of conversion within 2years |

| IL2RA (interleukin‑2 receptor alpha) | rs2104286 | ~1.4× increased risk |

| TNFRSF1A (tumor necrosis factor receptor) | rs1800693 | Modest effect, more evident with smoking |

| CD58 (cell adhesion molecule) | rs1414273 | ~1.3× risk elevation |

These genes all converge on immune regulation. HLA‑DRB1 influences antigen presentation, IL2RA modulates T‑cell activation, TNFRSF1A shapes inflammatory signaling, and CD58 affects immune cell adhesion. When any of these pathways are over‑active, the spinal cord or optic nerve can become a target for immune attack.

When Genes Meet the Environment

Genetic predisposition alone won’t guarantee a second attack. Environmental factors act like accelerators or brakes.

- Vitamin D: Low serum 25‑OH‑D (<20ng/mL) multiplies the effect of HLA‑DRB1*15. Studies from 2021‑2024 show a 30% higher conversion rate in vitamin‑D‑deficient CIS patients carrying the risk allele.

- Epstein‑Barr Virus (EBV): A prior EBV infection, especially infectious mononucleosis, raises MS risk by 2‑3×. When combined with high‑risk HLA alleles, the conversion odds climb even further.

- Smoking: Current smokers with the TNFRSF1A risk allele experience a synergistic increase in lesion load on MRI.

- Obesity in adolescence: Body‑mass index above the 95th percentile before age 20 has been linked to a higher genetic susceptibility score.

From a practical standpoint, the best strategy is to optimize modifiable factors: maintain adequate vitamin D, avoid smoking, and manage weight. Doing so can blunt the impact of high‑risk genes.

Should You Get Genetic Testing?

Genetic testing for CIS isn’t routine, but it can be useful in specific scenarios.

- Strong family history: If a first‑degree relative has MS, a genetic risk score (GRS) can help gauge personal risk.

- Uncertainty about prognosis: Patients anxious about conversion may opt for testing to inform follow‑up scan frequency.

- Clinical trials: Some research studies stratify participants by HLA‑DRB1 status; testing becomes a requirement.

Testing typically involves a saliva kit or a blood draw, analyzed by a certified lab. The result is a list of risk alleles and a composite GRS, expressed as a percentile (e.g., 85th percentile = higher than 85% of the reference population).

It’s essential to pair the lab report with genetic counseling. A high score doesn’t guarantee MS, and a low score doesn’t promise protection. Counselors translate the numbers into actionable monitoring plans.

Risk Assessment Tools You Can Use Today

Beyond raw genetic data, several validated calculators combine genetics with clinical variables.

- McDonald‑CIS Converter Score: Uses MRI lesion count, age, and HLA‑DRB1 status. A score above 0.6 predicts a 70% conversion risk at 2years.

- Genetic Risk Index (GRI): Incorporates 110 MS‑linked SNPs. Each SNP contributes a weighted value; the sum is normalized to a 0‑100 scale.

- Environmental‑Genetic Interaction Model: Adds vitamin D level and EBV serostatus to the GRI for a more personalized forecast.

Most neurologists use the McDonald‑CIS Converter Score because it’s quick and requires only standard MRI data plus HLA typing. If you’re considering testing, ask your neurologist whether they can calculate this score for you.

Implications for Treatment & Monitoring

Knowing a patient’s genetic risk can shape three key decisions.

- Frequency of MRI scans: High‑risk individuals may get a brain MRI every 6months instead of yearly.

- Early disease‑modifying therapy (DMT): Some clinicians start low‑efficacy DMTs (like interferon‑β) in high‑risk CIS patients even before a second clinical attack.

- Lifestyle counseling: A GRS result reinforces the importance of vitamin D supplementation (e.g., 2000‑4000IU daily) and smoking cessation.

Research from 2023‑2024 suggests that initiating DMT within 12months of a high‑risk CIS diagnosis can shave 15-20% off the long‑term disability accumulation.

Key Takeaways Checklist

- Identify CIS early with MRI and clinical exam.

- Ask about family history of MS - it raises suspicion of a genetic component.

- If you have a strong family history, consider HLA‑DRB1 typing and a GRS.

- Maintain vitamin D>30ng/mL; supplement if needed.

- Avoid smoking and manage weight to reduce gene‑environment synergy.

- Discuss with your neurologist whether early DMT is appropriate based on risk scores.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can genetics predict if I will definitely get multiple sclerosis?

No. Genetics tells you about probability, not certainty. Even people with a high‑risk genetic profile may never have a second attack, especially if they control modifiable risk factors.

Is HLA‑DRB1 testing covered by insurance?

Coverage varies by plan and region. Some plans consider it experimental unless you’re enrolling in a clinical trial. It’s worth checking with your insurer’s genetics benefits department.

How often should I get MRI scans if I have a high genetic risk?

For high‑risk patients, most neurologists recommend every 6months for the first two years, then yearly if no new lesions appear.

Does vitamin D supplementation lower my genetic risk?

It doesn’t change the DNA, but adequate vitamin D can dampen the effect of risk alleles like HLA‑DRB1*15, reducing the likelihood of a second attack.

Should I start disease‑modifying therapy right after a CIS episode?

If your risk score is high (e.g., McDonald‑CIS Converter >0.6) or you have multiple MRI lesions, many clinicians recommend early DMT. Discuss risks and benefits with your neurologist.

Understanding the link between clinically isolated syndrome and genetics equips you to make smarter health choices. While you can’t rewrite your DNA, you can control the environment, stay on top of monitoring, and work with your care team to decide whether early treatment makes sense.

Cierra Nakakura

October 2, 2025 AT 21:56Wow, this CIS risk calculator looks super handy! 🎉 If you're curious about your odds, just plug in the numbers and boom – you get a clear picture. Remember, lifestyle tweaks like boosting vitamin D and quitting smoking can actually shift that risk downward. 🚀 So don’t stress too much; use the tool as a guide, not a verdict. Good luck staying healthy! 😊

Sharif Ahmed

October 3, 2025 AT 02:06Ah, the nuanced interplay of HLA-DRB1*15:01 and MS susceptibility – a veritable symphony of molecular choreography. One cannot help but marvel at the elegant, albeit merciless, architecture of our genome.

Charlie Crabtree

October 3, 2025 AT 16:00Hey folks, diving into this calculator is like pulling back the curtain on your future health, and that’s both exciting and empowering!

First off, the age factor is a big deal – younger onset often means a higher baseline risk, but it also means you have more time to intervene.

Secondly, those MRI lesions are like breadcrumbs leading us to the underlying pathology, so counting them accurately is crucial.

Third, having a family member with MS can double or even triple your risk, which is why your genetic background matters a lot.

Speaking of genetics, the HLA-DRB1*15:01 allele is the heavyweight champion, increasing risk by up to threefold – that’s massive!

The IL2RA rs2104286 variant adds a modest bump, about 1.4 times the baseline, while TNFRSF1A and CD58 contribute their own subtle nudges.

Don’t forget vitamin D – keeping levels above 20 ng/mL can shave off a decent chunk of that risk score, so sunshine and supplements are your friends.

Smoking, on the other hand, is a nasty villain that can add nearly a whole point to your risk, so kicking the habit is a top priority.

Now, when you plug all these numbers into the calculator, you’ll see a composite risk that reflects the sum of these pieces, not just a single factor.

It’s important to interpret the result as a guide rather than a destiny; lifestyle changes can meaningfully shift the odds.

For example, quitting smoking and boosting vitamin D might lower your score from a ‘high’ to a ‘medium’ risk category.

Also, regular follow‑up MRIs can catch new lesions early, giving you a chance to adjust treatment plans swiftly.

Remember, the calculator’s maximum score caps at 5, so even if you’re walking the higher end, there’s still room for improvement.

If you’re feeling overwhelmed, talk to a neurologist – they can help parse the numbers and suggest personalized interventions.

Stay positive, stay proactive, and use this tool as a springboard to take charge of your health journey! 💪

And most importantly, keep sharing your experiences with the community – we all learn more together.

RaeLyn Boothe

October 4, 2025 AT 19:46Interesting to see how many variables they crammed into one calculator – makes you wonder what other hidden factors we haven’t even considered yet. The tool definitely pushes us to think beyond just the obvious MRI findings.

Fatima Sami

October 5, 2025 AT 23:33While the intent behind this CIS risk calculator is commendable, there are several grammatical oversights that merit attention. Firstly, the phrase “age at CIS onset (years):” should be followed by a consistent verb tense throughout the interface. Secondly, the instruction “Enter your information and click ‘Calculate Risk Score’ to see your estimated risk” employs an imperative mood that clashes with the otherwise descriptive tone. Moreover, the placeholder “Number of MRI lesions:” is ambiguous – a colon already implies a list, rendering the subsequent “None, 1, 2 or more” redundant. The usage of “vitamin D level (ng/mL):” lacks capitalization consistency, as “Vitamin D” is a proper noun. Additionally, the sentence “Smoking status (increases risk if yes)” is syntactically flawed; a more appropriate construction would be “Smoking status (yes increases risk).” The JavaScript comment “// Base calculation” is correctly prefixed, yet the subsequent conditional “else if (age >= 30 && age = 30)” contains a typographical error – the equality operator should be “==” or “===.” Furthermore, the line “else if (vitaminD >= 20) riskScore -= 0.2;” is placed after an unrelated condition, breaking logical flow. In the normalization step, the comment “// Normalize risk score” is helpful, but the variable naming could be more descriptive, perhaps “finalRiskScore.” The final display logic lacks a default case for risk scores below the “low” threshold, which could lead to an undefined presentation. Also, the HTML structure omits a closing tag for the result area, potentially causing rendering issues. The overall design would benefit from consistent capitalization, proper punctuation, and rigorous testing of conditional statements. Lastly, ensuring that each variable name is self‑explanatory would enhance maintainability for future developers. Implementing unit tests for each conditional branch would further guarantee reliability. Overall, a polished grammatical framework will make the tool more trustworthy to clinicians and patients alike.

Arjun Santhosh

October 7, 2025 AT 03:20Yo, the calculator's UI could use a bit more polish.

Stephanie Jones

October 8, 2025 AT 07:06The shadows of uncertainty loom large when confronting a CIS diagnosis, whispering doubts that echo in the mind’s corridors. Yet, each data point on this calculator is a candle flickering against that darkness, offering fleeting illumination. Let us not become slaves to the numbers, but seekers of meaning beyond the metrics.

Nathan Hamer

October 9, 2025 AT 10:53Behold! The intricacies of genetic predisposition unveil themselves in a dazzling tapestry of risk factors!!! 🎭

When you consider HLA‑DRB1*15:01, you’re staring into the abyss of a two‑ to three‑fold increase – an abyss that, with vigilant lifestyle choices, can be navigated.

Vitamin D, the sun’s generous gift, stands as a beacon: keep those levels north of 20 ng/mL, and you’ll shave precious points off the score.

Smoking? Ah, the insidious foe that adds nearly a whole point; banish it, and you reclaim control.

MRI lesions, those silent messengers, whisper their tale; the more you see, the louder the warning bell rings.

Family history, a genetic echo, can double or triple the risk, reminding us that destiny is often a family affair.

Yet, this calculator is not a prophecy; it is a compass, guiding you toward proactive health strategies.

Embrace the data, wield it wisely, and stride forward with confidence!!! 🚀

Tom Smith

October 10, 2025 AT 14:40Oh great, another “magic box” that tells you your fate – because we all love a good mystery, right? In all seriousness, the calculator does a decent job of aggregating known risk factors, but remember it’s only as good as the data you feed it. If you’re clueless about your vitamin D levels, perhaps start there before blaming genetics. And do yourself a favor: schedule a follow‑up with a neurologist – they’ll translate these numbers into a concrete plan, not just a flashy color‑coded badge.

Kyah Chan

October 11, 2025 AT 18:26The present CIS risk assessment instrument exhibits a multitude of methodological shortcomings that warrant rigorous scrutiny. Firstly, the algorithmic weighting lacks transparent justification, rendering the resultant risk scores opaque to both clinicians and patients. Secondly, the interface neglects to implement input validation for numerical fields, thereby exposing the system to erroneous entries. Moreover, the reliance on a static set of genetic markers fails to accommodate emerging polymorphisms identified in recent genome‑wide association studies. The omission of confidence intervals further diminishes the utility of the output, as users are unable to gauge the statistical certainty of the predictions. In addition, the absence of a comprehensive user guide contravenes best practices for clinical decision support tools. Consequently, while the calculator may serve as an introductory adjunct, its deployment in a clinical setting must be approached with circumspection.

Ira Andani Agustianingrum

October 12, 2025 AT 22:13Hey there! I see you’re exploring the CIS risk calculator, and that’s a fantastic first step toward taking charge of your health. Remember, the numbers are just a guide – think of them as a starting line, not the finish. Keep an eye on your vitamin D, stay active, and consider quitting smoking if it applies to you; every positive change can tip the scales. If you ever feel uncertain, reaching out to a neurologist or a support group can provide clarity and encouragement. You’ve got this, and the community is here to cheer you on every step of the way! 🌟