Grief Assessment Tool for Sickle Cell Community

How are you feeling?

This tool helps you identify if you're experiencing complicated grief. Answer these questions based on your recent experiences. The tool won't share your data or identify you.

When a loved one with Sickle Cell Anemia is a hereditary blood disorder that causes chronic pain, frequent crises, and shortened life expectancy passes away or faces serious complications, the grief can feel uniquely intense. The community often carries the weight of shared loss, cultural expectations, and medical uncertainty. Below is a step‑by‑step guide to recognizing, processing, and easing that grief while staying connected to the support systems that matter most.

Why Grief Looks Different in the Sickle Cell Community

People with sickle cell disease (SCD) and their families experience a cycle of anticipatory loss-each painful crisis is a reminder that life can change suddenly. This makes traditional mourning stages (denial, anger, bargaining, depression, acceptance) blend together, creating a chronic grief background rather than a single event.

- Repeated hospitalizations keep families in a state of heightened stress.

- Stigmatization can limit open discussion about emotional pain.

- Genetic inheritance means loss may affect multiple generations simultaneously.

Understanding these nuances helps you avoid judging your own feelings or those of others as “over‑reacting.”

Spotting Complicated Grief Early

Most grief eases over months, but complicated grief lingers past six months and interferes with daily functioning. Look for these red flags:

- Persistent yearning for the person that disrupts work or school.

- Intense guilt about decisions made during the illness (e.g., treatment choices).

- Withdrawal from community events that were once central.

- Physical symptoms such as insomnia, headaches, or worsening pain crises.

If several of these appear, consider reaching out to a mental‑health professional who understands both grief and chronic illness.

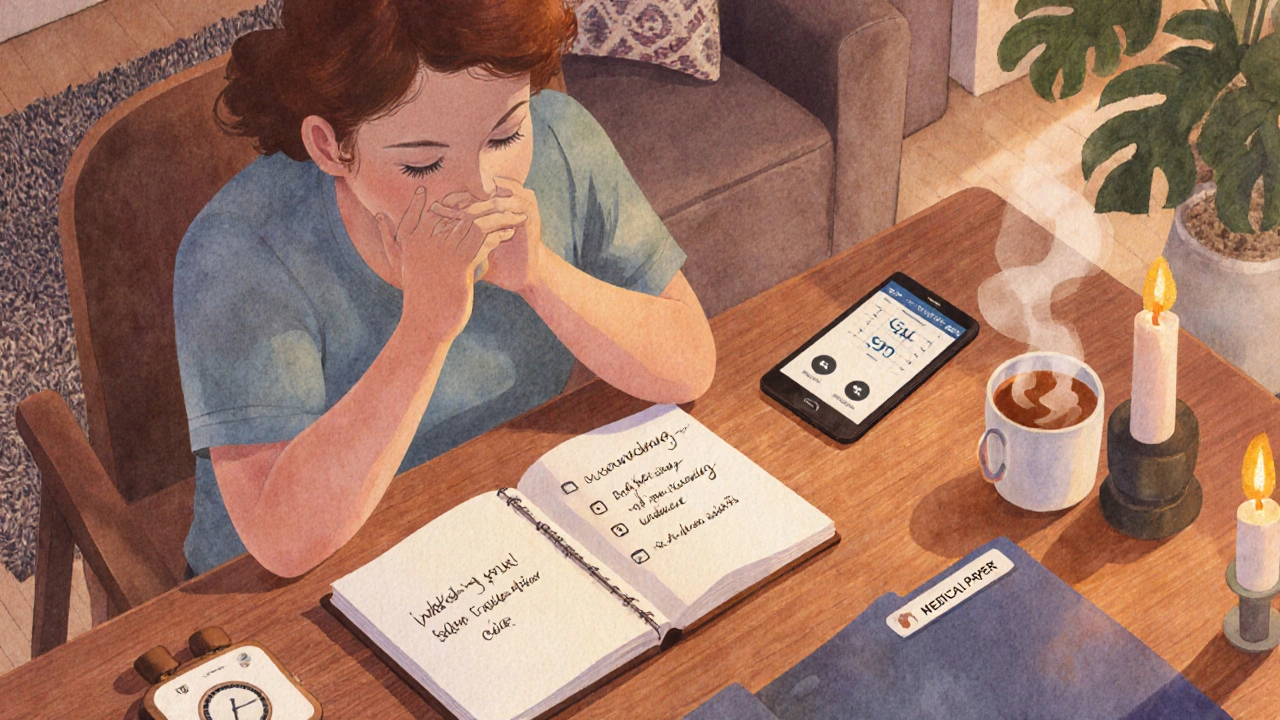

Immediate Coping Steps After a Loss

When shock hits, the brain can’t process information clearly. Ground yourself with these concrete actions:

- Take a breath. Inhale for four seconds, hold for four, exhale for six. This simple rhythm lowers cortisol.

- Call one trusted person-a family member, a church friend, or a community liaison.

- Write down the first three thoughts that come to mind; externalizing them reduces rumination.

- Secure any medical paperwork (hospital discharge, autopsy report) in a safe folder for later review.

These steps create a small sense of control when everything feels chaotic.

Building a Support Network That Works for You

Support can come from many directions. Here’s a quick checklist to assess what’s available and what still needs to be added:

| Type | What It Offers | How to Access |

|---|---|---|

| Peer Support Group | Shared stories, validation, coping tips from families who understand SCD. | Contact local chapters of the Sickle Cell Disease Association of America (SCDAA) or ask your hematology clinic. |

| Professional Counseling | Evidence‑based therapies (CBT, grief counseling) tailored to chronic‑illness stress. | Ask your insurance for a mental‑health referral; many therapists specialize in medical bereavement. |

| Online Community Forums | 24/7 anonymity, quick answers, resource links. | Platforms like Reddit’s r/sicklecell or dedicated Facebook groups. |

| Faith‑Based or Cultural Centers | Rituals, prayer, cultural practices that honor the deceased. | Reach out to local churches, mosques, or community elders. |

Mixing at least two of these sources creates a safety net that can catch you when one avenue feels empty.

Professional Help: What to Expect

Finding a therapist who “gets” sickle cell grief isn’t always straightforward. Here’s a quick guide to vetting potential providers:

- Ask for experience with chronic‑illness or pediatric loss.

- Check credentials: look for licensure, and if possible, certification in grief counseling (e.g., CGC).

- Confirm they understand the cultural context of your family-some therapists specialize in African‑American health disparities.

- Schedule a brief “consult” session to see if their style feels supportive.

If insurance is a barrier, many hospitals offer sliding‑scale services. The SCDAA provides a directory of vetted mental‑health professionals experienced with sickle cell families at no cost.

Everyday Self‑Care Practices That Reduce Grief Overload

Grief isn’t a one‑time event; it’s a daily rhythm. Incorporate these habits to keep the emotional tide from overwhelming you:

- Physical movement. Even gentle stretching or a short walk releases endorphins that counteract sorrow‑related fatigue.

- Nutrition focus: omega‑3 fatty acids (found in salmon, flaxseed) have modest anti‑depressive effects.

- Sleep hygiene: keep a consistent bedtime, limit caffeine after 2p.m., and use a white‑noise app if hospital sounds linger.

- Mindful journaling: write one thing you’re grateful for each day, even if it’s a memory of the loved one.

- Creative outlet: art, music, or cooking a family recipe can transform pain into a tribute.

These practices aren’t a cure, but they form a resilient baseline that makes professional therapy more effective.

Resources and Community Organizations

Below is a curated list of reputable groups that offer grief‑focused services for the sickle cell community. Most have both national reach and local chapters.

- Sickle Cell Disease Association of America (SCDAA) - offers bereavement webinars, a 24‑hour helpline, and a peer‑mentor matching program.

- National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) - provides grief groups that welcome chronic‑illness families.

- The Center for Disease Control (CDC) - publishes research on coping mechanisms for families affected by genetic blood disorders.

- Local Hospital Social Work Departments - often have dedicated sickle‑cell case managers who can connect you with counseling services.

- Faith‑Based Grief Ministries - many churches in Chicago run “Healing Circles” that honor the loss of children with chronic illness.

Reach out to at least one of these groups within the next two weeks; the act of contacting a resource can itself be therapeutic.

Putting It All Together: A Simple 7‑Day Action Plan

- Day 1: Write down the top three emotions you’re feeling. Keep the list somewhere visible.

- Day 2: Call a peer‑support group leader and attend a virtual meeting.

- Day 3: Schedule a consultation with a therapist who specializes in medical grief.

- Day 4: Choose a self‑care activity (walk, yoga, cooking) and devote at least 30 minutes to it.

- Day 5: Compile all medical documents in a folder; note any questions for the hematologist.

- Day 6: Write a short tribute-photo collage, poem, or letter-to celebrate the lost loved one.

- Day 7: Review your journal entries; notice any shift in tone or intensity. Adjust the next week’s plan accordingly.

Following a concrete plan stops grief from feeling like a free‑floating mess. Adjust each step to fit your personal rhythm, but keep the momentum going.

Frequently Asked Questions

How soon should I seek professional help after losing someone with sickle cell?

If you notice persistent sadness, trouble sleeping, or inability to attend daily responsibilities for more than six weeks, reach out to a therapist. Early intervention prevents complications like depression or prolonged anxiety.

Can I join a grief group if I’m not a patient myself?

Absolutely. Many groups welcome family members, friends, and even coworkers because they all share the emotional impact of the disease.

What are signs that my grief might be turning into depression?

Key indicators include loss of interest in previously enjoyable activities, feelings of hopelessness, significant weight change, and thoughts of self‑harm. If any appear, contact a mental‑health professional immediately.

Are there specific therapies proven helpful for medical bereavement?

Cognitive‑behavioral therapy (CBT) adapted for grief, narrative therapy, and dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) for emotional regulation have strong evidence. Look for clinicians who list “medical bereavement” as a specialty.

How can I support a friend who is grieving a sickle cell loss?

Listen without trying to “fix” the pain, offer concrete help (meals, transportation), and check in regularly. Respect cultural rituals, and avoid clichés like “they’re in a better place.”

Edwin Pennock

October 12, 2025 AT 03:20Sure, but have you considered that most of these ‘resources’ are just corporate fluff?

John McGuire

October 12, 2025 AT 04:43Wow, this guide is a lifesaver! 😃💪 If you’re feeling overwhelmed, jump on a peer‑support call right now and remember you’re not alone. 🌟

newsscribbles kunle

October 12, 2025 AT 06:06In my country we don’t need foreign “associations” telling us how to grieve – our families are the backbone, and no outsider understands the true pain of a sickle‑cell loss!

Bernard Williams

October 12, 2025 AT 07:30What really helps is turning the endless medical appointments into a structured routine.

First, write down the top three emotions you feel each morning – that simple act of naming the feeling reduces its power.

Second, schedule a 15‑minute walk or gentle stretch; movement releases endorphins that counteract the grief‑induced fatigue.

Third, set up a weekly virtual meetup with a local SCDAA chapter – hearing others share their stories creates a safety net you can lean on.

Don’t forget to keep all medical paperwork in one folder; it’s amazing how much mental space you free up when you know where everything is.

Finally, if the grief feels stuck after a month, reach out to a therapist who lists medical bereavement as a specialty – they can teach you CBT techniques tailored to chronic‑illness loss.

Mixing at least two of these supports, as the article suggests, builds resilience and keeps you from feeling isolated.

Michelle Morrison

October 12, 2025 AT 08:53One must question the hidden agendas behind these so‑called support groups – are they truly for grieving families, or merely data‑mining enterprises seeking to profit from our pain? The truth, of course, is cloaked beneath layers of bureaucratic language.

harold dixon

October 12, 2025 AT 10:16I appreciate the thoroughness of the guide; one practical tip I’d add is to set a reminder on your phone for a daily “check‑in” with yourself – note any spikes in anxiety and then reach out to a trusted friend if needed.

Darrin Taylor

October 12, 2025 AT 11:40Honestly, all these steps sound like a corporate wellness program designed to keep us productive rather than truly heal. 🙄 If you’re looking for real comfort, maybe consider stepping away from the endless webinars.

Anthony MEMENTO

October 12, 2025 AT 13:03People need to understand that grief is not just a feeling its a physiological response that can exacerbate sickle‑cell pain management strategies if not addressed properly the body remembers trauma and reacts by increasing cortisol which in turn can trigger more pain crises it’s essential to have a multidisciplinary approach involving hematologists mental health professionals and community leaders to break this cycle

aishwarya venu

October 12, 2025 AT 14:26Such a comprehensive guide! I especially love the 7‑day action plan – it gives a clear path forward and feels very hopeful.

Nicole Koshen

October 12, 2025 AT 15:50Great article overall. A small note: “It’s” should have an apostrophe in “It’s important” and “don’t” needs one as well. Also, consider using commas after introductory phrases for better flow.

Ed Norton

October 12, 2025 AT 17:13Thanks for the info. Very useful.

Karen Misakyan

October 12, 2025 AT 18:36From a philosophical standpoint, grief can be viewed as an existential confrontation with finitude; the structured coping mechanisms outlined herein serve not merely as palliative measures but as ontological recalibrations that re‑anchor the self within a community of shared mortality.

Amy Robbins

October 12, 2025 AT 20:00Oh, look, another “step‑by‑step” guide that pretends to solve deep emotional trauma with a checklist. Because nothing says “I care” like a bullet point list.

Shriniwas Kumar

October 12, 2025 AT 21:23Integrating community‑based participatory research (CBPR) frameworks into grief interventions can foster culturally resonant support structures. By leveraging indigenous epistemologies and health‑belief systems, we create a synergistic model that aligns biomedical protocols with sociocultural praxis, thereby enhancing therapeutic adherence among sickle‑cell families.

Jennifer Haupt

October 12, 2025 AT 22:46When I first read the sections on “Complicated Grief,” I was struck by the stark reminder that grief is not a linear trajectory but a multidimensional experience shaped by cultural narratives, biological imperatives, and personal histories.

Consider, for a moment, the way our societies assign meaning to loss: some view it through the lens of religious ritual, others through the prism of medical pathology.

This duality necessitates a hybrid approach-one that honors the somatic realities of sickle‑cell pain while also acknowledging the metaphysical void left by a loved one’s departure.

The 7‑day action plan, while pragmatically sound, could benefit from an explicit acknowledgement of the role of narrative reconstruction; encouraging mourners to rewrite their story with the deceased as a continuing influence rather than a final chapter.

Moreover, the recommendation to seek “therapists who specialize in medical bereavement” should be expanded to include providers trained in narrative therapy, which has demonstrated efficacy in integrating loss into a cohesive self‑identity.

On a practical level, the suggestion to “secure medical paperwork” is brilliant yet under‑emphasized; having that tangible record can serve as an anchor during moments of dissociation.

In addition, the guide’s emphasis on physical movement aligns with emerging research linking aerobic activity to neurogenesis and emotional regulation-key factors in mitigating the physiological stress response inherent in grief.

However, it stops short of addressing the socioeconomic barriers many families face; not all can afford a therapist or even a safe space for exercise.

To truly embody inclusivity, the resource list should highlight low‑cost community centers, sliding‑scale clinics, and tele‑health options that operate on a donation basis.

Finally, the call to “mix at least two sources of support” is essential, yet the guide could provide a decision‑tree to help individuals assess which combinations best fit their unique circumstances-be it peer support plus faith‑based counseling, or professional therapy supplemented by creative arts groups.

In essence, grief support for the sickle‑cell community must be as dynamic and resilient as the individuals it aims to serve, weaving together biomedical, psychological, and cultural threads into a tapestry of hope.